Many years ago I worked alongside the sales team of a B2B2C financial services company. The Sales Director was getting frustrated at the lack of sales being closed, and became even more frustrated when he discovered that his sales managers weren’t sticking to the agreed script when they went out to see prospects.

He’d had a mooch around the common drive and found that his sales managers were editing the “official” sales doc to suit their own presentation style.

This, clearly, would not do.

To counter this, he locked the “official” sales deck, and told his sales managers to use this version so that they couldn’t deviate from the narrative he believed was best to make a sale.

This puzzled me.

Surely the best sales people – even when they only have one solution to sell – position that solution so that in some way it meets the needs of the person they’re selling to.

The Sales Director was having none of it. His team were to sell his way, or not at all.

So far, so not-very-good.

Why your standard sales aid deck may not be an aid at all

In due course, the old Sales Director moved on, and an external candidate was brought in to shake things up. I sat alongside the new guy in his first sales pitch, as I was going to be the manager responsible for onboarding the new client if the sale was closed.

When we met at the client’s offices before the meeting, I asked him if he was going to be using the ‘mandated’ sales deck to present from.

“I’m not presenting from any deck, Simon” he told me. “I’m just going to ask our prospect a few questions”.

And ask he did.

After the usual “Hi-how-are-you” pleasantries, his opening question to the prospect was “So help me understand a little about how things are going here – can’t be easy in the current market?”

And so thus prompted, the client happily opened up to talk about market share, cost challenges, compliance challenges, budget challenges and the like.

And each time the prospect paused, the new Sales Director would nod; offer up a relevant market-related insight of his own; and asked the prospect to continue.

What fascinated me was that in the absence of a sales deck to talk to, the eye contact between the prospect and the Sales Director was pretty constant.

I’d never thought of a sales deck as being a distraction before – I’d always thought it was a framework around which a sales manager would build their argument.

Not here.

Instead, a meeting that under the old Sales Director’s mandate would have been a lecture (“I’m gonna talk, and you’re gonna listen!”) the prospect and the new Sales Director had a discussion.

Using insight to lead the witness

It was clear from the tone of the discussion that the prospect was engaged and felt he was being listened to from the start.

But what was also curious was the direction the discussion was going.

Because the other thing that became quickly clear as the meeting progressed was that the new Sales Director had done a lot of prep.

He’d read up on the prospect and his boss via LinkedIn and trade press mentions.

He’d read up on the prospect’s business – market share, revenues, company report, and in particular the CEO statement that talked directly about the strategic direction he wanted to take the business.

But most intriguingly, he’d read up on the client’s incumbent provider, and done his own research on where they were vulnerable: in this case, high complaints levels, unmet promises, and slow service delivery.

So – not unlike a good prosecuting lawyer facing a guilt-ridden defendant – before he even asked a question, he knew what the prospect was going to say.

Which meant that over the course of perhaps 45 minutes, he was gently able to guide the prospect into saying that they had a range of challenges where the incumbent was under-performing – pretty much all of which could be solved in some way by what the Sales Director was there to sell him.

Why this is important

The way that meeting was conducted was quite revelatory for me.

Many of the key things I learned then I still apply today:

Sales is a dialogue, not a monologue. No one can be lectured into buying – not in B2B, anyway.

The phrase “Help me understand…” is one of the best opening lines you can use in a sales meeting.

Maybe leave the deck at home: promise to send it after the meeting so the prospect has something evidential to show their stakeholders?

But most importantly, if you want to sell to need, researching where the prospect is currently being sold short can be surprisingly lucrative.

Selling to weakness

Not all incumbents are weak in the same areas, of course.

Some will have poor post-sale implementation.

Some will have high ongoing running costs.

Some may be particularly poor at servicing a particular vertical, or a particular territory.

Some may not actually solve for the key issue they were appointed to solve.

However, not every sales manager has the time or resource to uncover empirical evidence of each competitor’s specific weaknesses in sufficient depth.

This is where having independent research can pay dividends, and where clients often engage me to help them.

I speak to their key competitors’ clients.

I ask them where they are happy with their incumbent provider.

Then, more importantly, I then ask them where they’re unhappy.

Over a period of interviews – either quantitative or qualitative, depending on the brief – I’m able to build a comprehensive view of which competitors are weak, and where, and what a competing vendor (that’s you, by the way) might need to offer to get them to switch.

Clients get a detailed report on the findings that tells them what propositions to lead with when pitching against each of their key competitors.

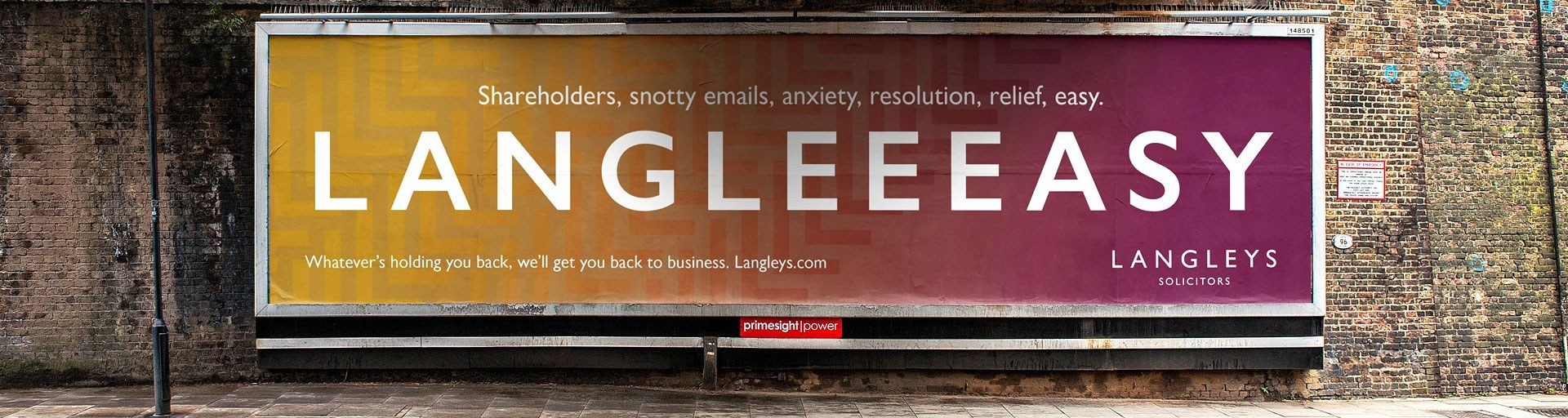

Which mean that instead of sticking to the standard script, sales managers can ask the pertinent questions most likely to gain traction with their prospect.

Because the easiest sales to close are the ones where your weaker competitors have left the sale wide open.

Need help?

If you want help researching where your own B2B competitors are weak, please get in touch.

Although based in the UK I work with clients internationally.

I’ve worked in B2B marketing for 25 years, and so readily understand the business context in which the research is being commissioned.

It also means that the recommendations and conclusions I draw are grounded in business reality.

I’ve access to a very wide panel of B2B business contacts that stretch across technology, professional services, engineering, financial services and beyond.

Leave me to find the areas where your rivals are weakest, and then leave your sales managers to exploit them.

Simon Hayhurst

“Sale” photo by Arno Senoner on Unsplash